The 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence is an annual campaign that kicks off on 25 November, the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, and runs until 10 December, International Human Rights Day.

But when we talk about gender-based violence (GBV) and how to end it, it is important to remember how complex the matter is – the many forms that violence can take and the factors that drive it. In Zimbabwe, intimate partner violence (IPV) is the most reported form of GBV. To address IPV and other forms of GBV, the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office has funded the Stopping Abuse and Female Exploitation (SAFE) programme.

As the lead of SAFE’s Evaluation and Learning Unit (ELU) – a key component of the programme – we provide robust evidence to our partners to find out what works to prevent – and efficiently respond to – GBV. In this blog, Hind Mhamdi, Consultant in our Monitoring, Evaluation, Research and Learning practice, gives insights into what we have learned so far about the social norms that drive GBV in Zimbabwe.

So far, the SAFE ELU team has completed evaluation and learning activities. After completing our first deep-dive study on social norms that influence IPV and child marriage, we conducted a quantitative baseline study to inform the programme design. Through a second deep dive study, we have established the baseline for a qualitative longitudinal cohort study that will track participants throughout the programme and follow up with them at programme completion.

These studies have yielded valuable insights of which our SAFE ELU team has selected a few we are pleased to be sharing:

Five key insights

Entrenched gender and social norms are instrumental in driving IPV

Our first two deep dive studies highlighted the link between IPV and expectations towards gender in intimate partner relationships. These expectations create conditions where violence against women can be perpetrated in private and justified as ‘punishment’ due to the uneven power dynamics within the partnership. Most community members perceive this form of violence as a private, household matter – discussing it outside of the household is neither encouraged nor accepted.

Examples of gender and social norms that drive IPV and its acceptability include:

- Men are the heads of the household and have the right to discipline their wives.

- Men are the household decision makers.

- Household labour and responsibilities are mostly relegated to women, while men are supposed to provide economically for their wives and families.

- Community members, particularly in urban areas, condemn physical violence more than other forms of violence, especially sexual IPV. Sexual and physical IPV are often linked to the gendered expectations that women are responsible for providing sex to their partners. If women refuse sex, both types of violence are seen as justifiable.

When violence is justified or accepted, it is linked to power, hierarchy and value within intimate partner relationships

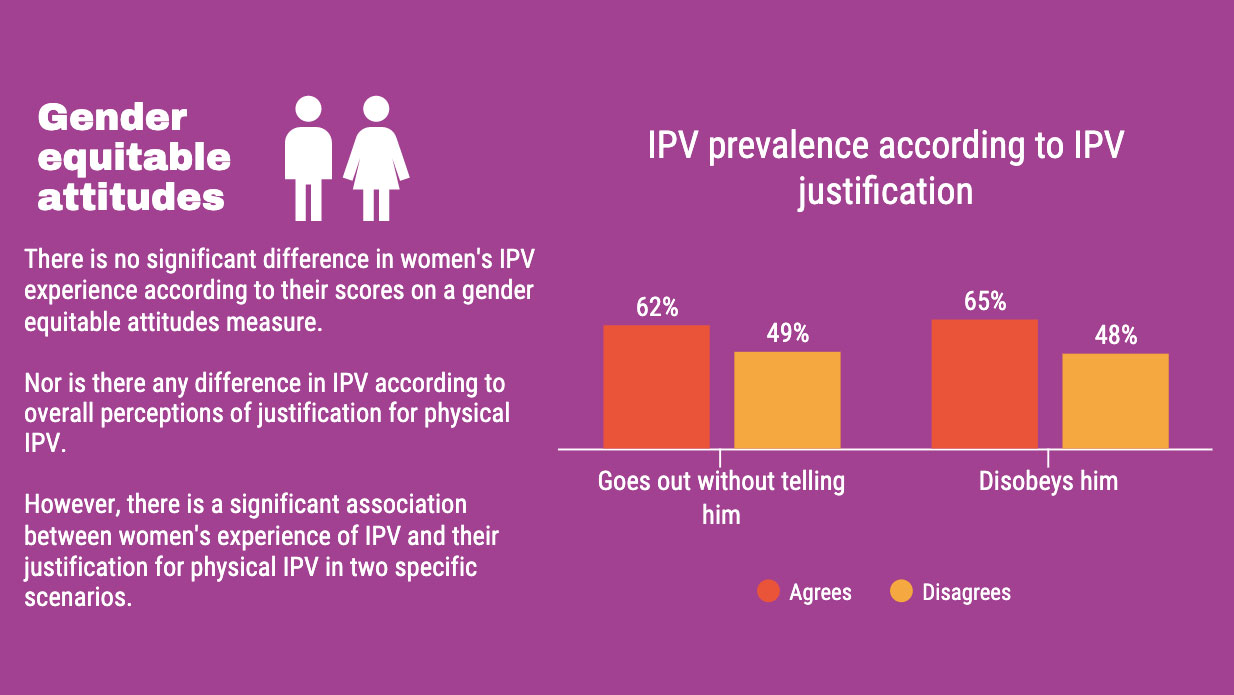

Violence is seen as justifiable when women transgress the power relations within their intimate partner relationship. For our baseline study, we looked at a wide range of scenarios that examined the relationship between women’s IPV experience and justification for physical IPV. We found a significant association between IPV experience and perceptions that it is justified for a man to beat his wife or partner if she disobeys him or goes out without telling him.

There is a strong relation between IPV and economic stress

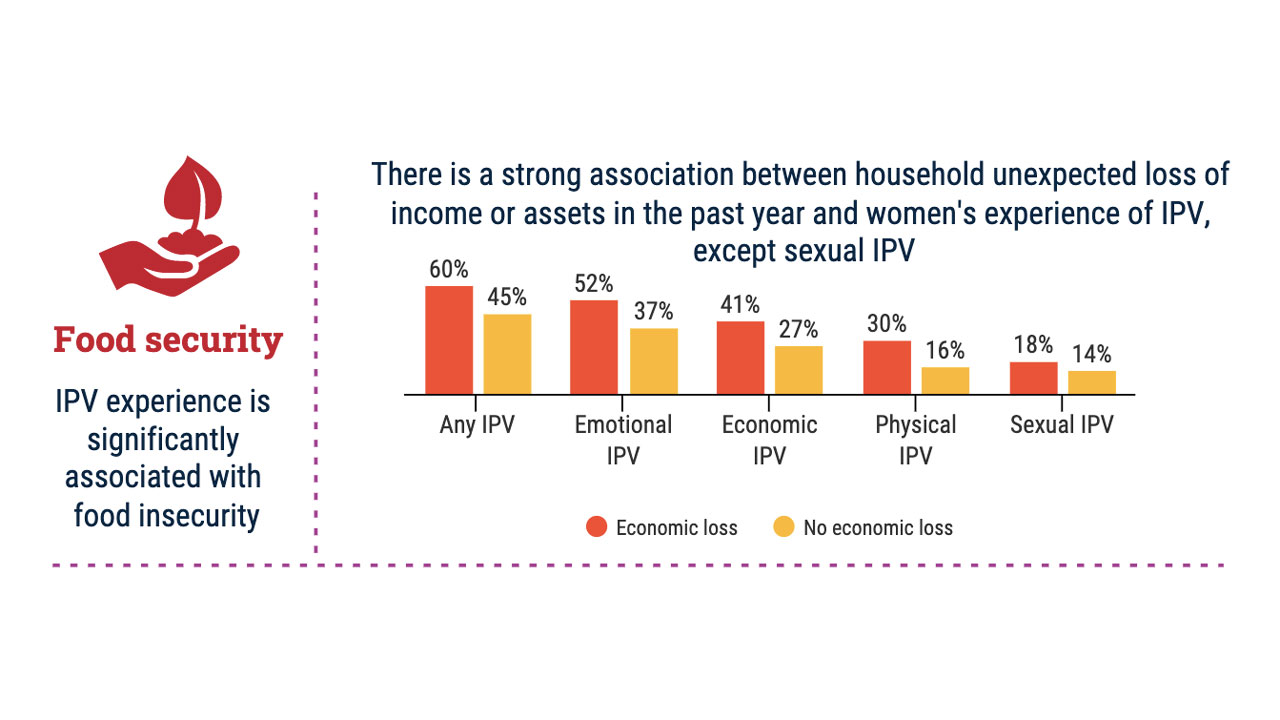

Our baseline study found a significant association between household food insecurity and women’s past 12-month experience of IPV. Similarly, women were more likely to have experienced IPV in the past 12 months when there was an economic shock in their household – such as an unexpected loss of income or assets – in this timeframe.

IPV is lower in couples who use dialogue and respectful conversations to resolve conflict and in couples that engage in joint decision making

IPV decreases when women and their partners make joint decisions about major household purchases and about how each partner’s earnings are spent. Generally, the more economic planning there is in a household, the less IPV occurs. Couples who engage more in non-violent conflict resolution and communication also experience less IPV.

Men’s frequent alcohol consumption and IPV are strongly associated

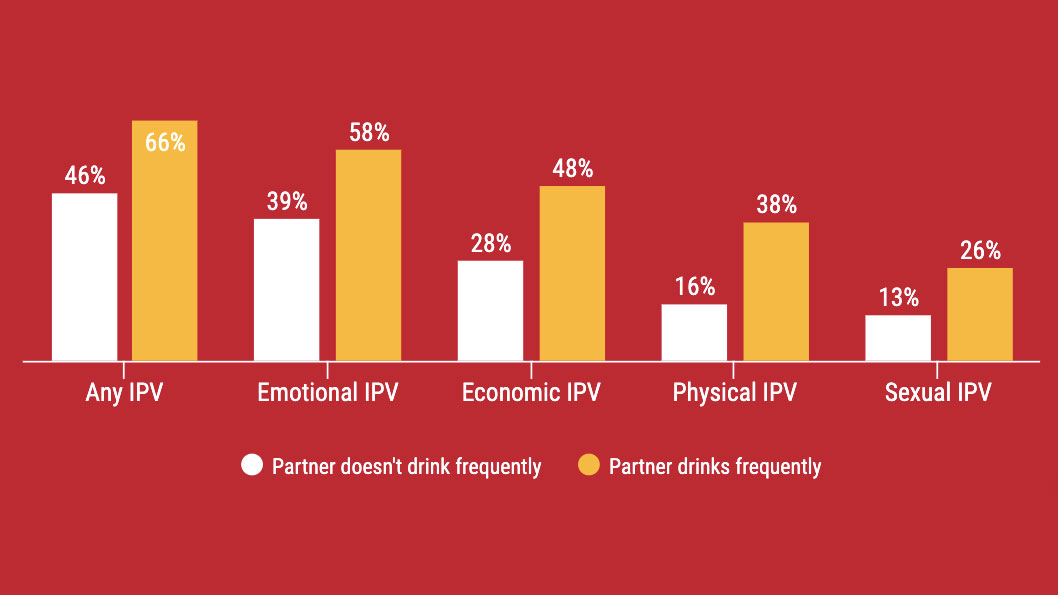

Our baseline study found a very strong association between women’s past 12-month IPV experience and their partner’s frequent alcohol consumption. Of those women whose partners drink, 47 percent had quarrelled with their partner about their drinking in the past year. Just over half of the women who had quarrelled said that this occurred because of their partner spending money on alcohol.

Our commitment to keeping women SAFE

This 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence, we are united in our call to keeping every woman and every girl safe from harm. But for us, the team behind SAFE’s Evaluation and Learning Unit, the campaign also comes as a strong reminder that the more evidence we have and the better we understand GBV and the factors that drive it, the better we are equipped to make a difference.

Only recently, for example, we completed our full baseline report. And with many more SAFE studies and reports to come and many more lessons to be learned, we are committed to sharing our insights that will help reduce GBV in Zimbabwe and beyond.